- Lump Sum or Stipulated Sum Fee

- Fee as a Percentage of Construction Cost

- Hourly Fees

- Unit Cost: $/SF

- Architect’s Basic Services

- Supplemental Services

- Additional Services

- Know Your Value

- Define Scope of Services

- Understand Level of Effort

- Factor in Risk

- Carry a Contingency

- Adjust for Your Tendencies

- Monitor Metrics and Historical Data

- Build Checklists

- Building a Bottom-Up Fee

- Building a Top-Down Fee

- Building a Staffing Level Fee

- Building a Unit Cost Fee

- Always Use Multiple Methods

- Get a Second Opinion

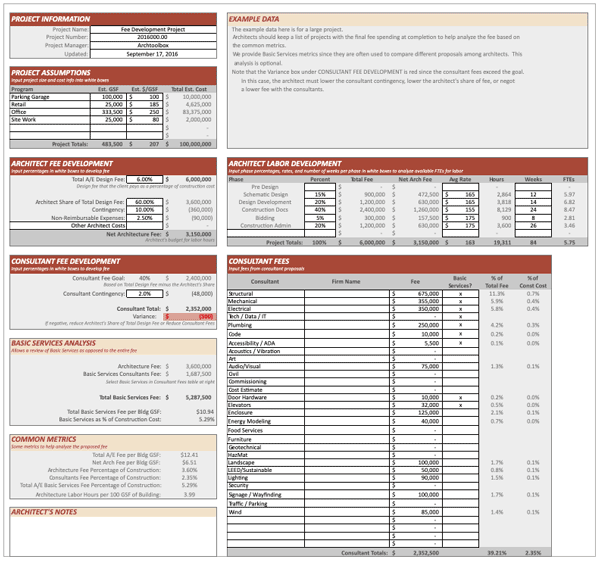

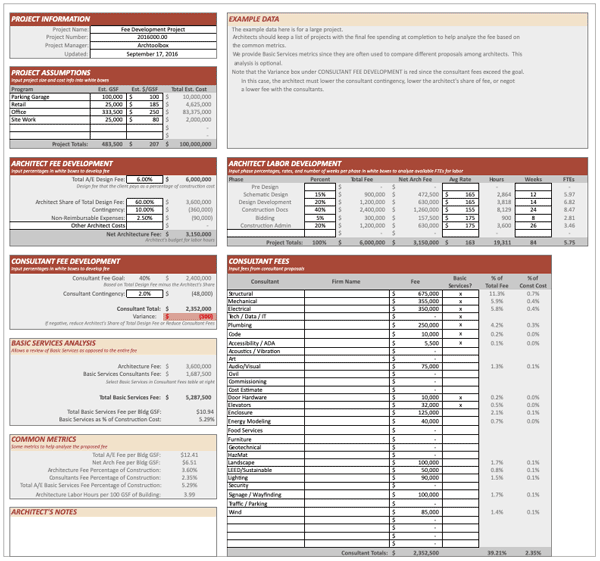

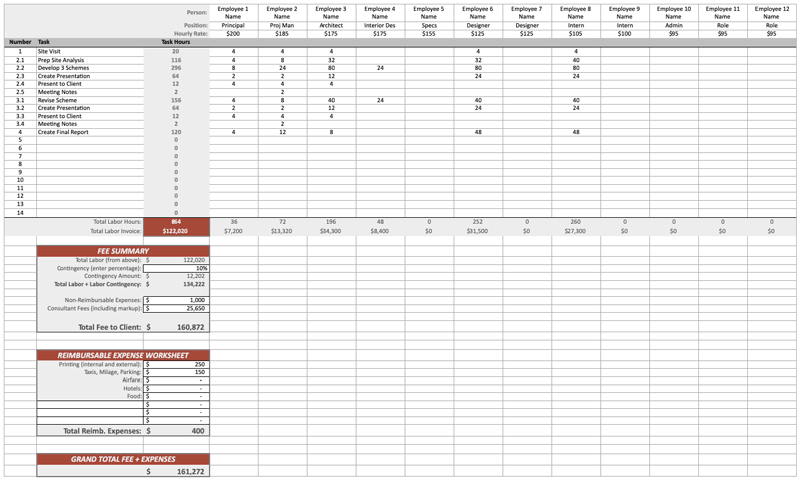

- Example Worksheets

- Commercial

- Residential

We will cover the four types of fee structures, what is and is not included in standard fees, a series of principles to consider when developing an architectural design fee, and then we discuss four ways to build a competitive and profitable fee.

Architects, interior designers, and engineers should be fairly compensated for the value they offer, the risks they carry, and the effort they apply to a project. Fee development takes all of those into account.

Architect's Fee Structure

There are four main compensation structures used in the industry. The AIA B101 Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Architect includes options for Stipulated Sum (often called Lump Sum), Percentage Basis, or any other method agreed to by both parties. The most common alternate to stipulated sum or percentage basis is an hourly fee, but there are some regions and project types where fees are calculated on a unit cost basis.

Lump Sum or Stipulated Sum Fee

A stipulated sum fee is a fixed fee for a set of services as defined in the contract. The owner and architect agree to the scope of services and the associated fee for that scope.

Owners like a stipulated sum fee because they can establish a fixed budget at the beginning of the project and everything is included if the scope of services is well defined. However, owners have to properly manage their decision making process to avoid changes in scope, which will lead to additional services costs. The architect is contractually obligated to identify additional services before starting work on them so the owner has a chance to avoid those fees if possible.

Architects can benefit from the stipulated sum structure since they know what they will be paid and can increase their profit by being more efficient. However, the architect carries the risk of underestimating the amount of work required to provide the instruments of service. An inefficient design and documentation process can lead to increased costs that cannot be passed along to the owner.

As we will discuss below, it is absolutely critical that the scope of services is well defined to limit exposure for all parties. Both the owner and architect should be keenly aware of what services are included and what are excluded to avoid contentious debates. Architects must also maintain good communication channels with the owner so they can preemptively warn when the owner’s decisions or process starts to affect the agreed scope.

Fee as a Percentage of Construction Cost

A less common method of compensation is the fee as a percentage of the owner’s cost of the work, often referred to as a fee based on percentage of construction cost. This method was much more common historically when the AIA published recommended fees based on construction cost, building type, and complexity. However, the AIA agreed to stop providing those recommendations.

The biggest drawback for both owner and architect is that the design fee can fluctuate significantly over the duration of the project as scope is added or removed and as market demand for construction fluctuates. Owners also worry that the architect has little incentive to look for cost reduction opportunities since their compensation increases when the building costs more.

The architect is protected from scope reductions through contractual language that indicates the fee is updated based on the most recent budget or estimate and past payments are not affected by those updates. Therefore, the owner can’t claw back fee as they reduce cost of the work.

While the percentage of construction cost method of setting compensation is not used as often as the lump sum method, owners and architects still use the general process to guide establishment of a lump sum fee. Most savvy owners know their estimated construction cost and can extrapolate their design fee based on a percentage. Likewise, most architects have an understanding of how their fees relate to construction cost as a percentage. This gives a good baseline to use when developing a stipulated sum fee.

Hourly Fees

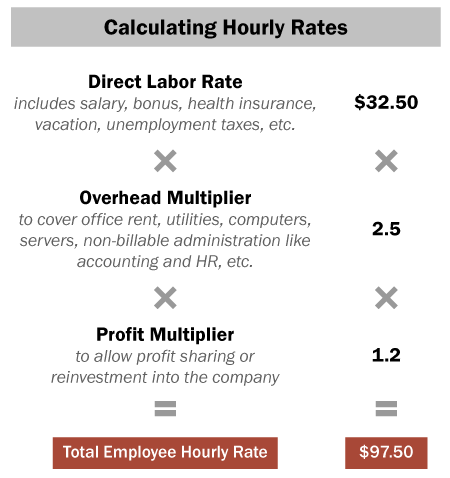

Hourly rates are very straightforward in that employees are assigned a billable rate and the owner is charged for each hour of work.

It is important to understand how hourly rates are developed and what they cover. The diagram below shows what goes into an hourly rate. Start with the direct labor rate, adjust with an overhead multiplier, and adjust again with the profit multiplier. Note that the multipliers vary by firm and are established with their own complex calculations.

When an hourly rate is developed correctly, it becomes the building block that allows any employee or project manager to build a fee that includes all overhead, profit, and labor expenses. Many designers argue that the hourly fee doesn’t properly factor in the value provided, but others argue that the direct labor rate includes the value that a person provides.

Owners often feel like an hourly fee is an open checkbook for the design team to work inefficiently, so they tend to avoid using this structure. Hourly fees also make budgeting hard for the owner. However, it is useful when the scope of services is not easily defined. For instance, the owner may engage an architect in a pre-design process to help develop the overall scope of work, which then gets assigned a stipulated sum fee. Another example is work associated with a municipality’s entitlements process, which is often hard to define.

A way of managing an hourly fee is to define a cap, often referred to as an Hourly Not-to-Exceed Fee or an Hourly Fee with Upset Limit. In this case, the design team develops an estimated level of effort for the project and assigns employees with their billing rates. Once the owner agrees and the work commences, the architect tracks all hours and charges the owner up to the agreed limit. The architect is not entitled to the full fee, but only invoices for the hours worked. The upper limit can be amended if both parties agree to continue services through written approval.

Unit Cost: $/SF

Although uncommon, it is possible to develop a design services fee based on a unit cost. The best example of this is dollars per square foot. A unit cost is highly dependent on the type and complexity of the project.

Regardless of whether a firm offers its services on a unit-cost basis, it is helpful to keep unit cost metrics as a means of validating other fee development processes. We cover metrics in more detail below.

Understanding Scope of Services

The AIA contracts define three different scopes of services: Basic Services, Supplement Services, and Additional Services. It is important to understand who is responsible for what parts of a project so that a proper fee can be assigned to the work.

Architect's Basic Services

The scope of an Architect’s Basic Services is laid out in Article 3 of the AIA B101 Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Architect. While this is the standard form of agreement used by many firms and clients, the draft contract should be reviewed before finalizing the fee since some owners use modified versions or completely different agreements.

The AIA documents include the following phases as part of Basic Services:

- Schematic Design

- Design Development

- Construction Documents

- Procurement (formerly Bidding and Negotiation)

- Construction (commonly called Construction Administration)

Architects are required to include structural, mechanical, plumbing, and electrical engineering services (usually through a consultant) during the design phases listed above. Other basic services include maintaining the design schedule, assisting in applying for permits, and providing basic cost estimates (detailed cost estimates are usually a supplemental service or are provided by a consultant hired directly by the owner).

Supplemental Services

The B101-2017 version of the Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Architect includes a new section in Article 4 called Supplemental Services to help separate them from Additional Services, which are added after the contract is executed.

B101-2017 includes a list of 30 Supplemental Services that may be required for a project. Each service is assigned to either the architect or the owner and the contract language allows for the addition of other Supplemental Services as required by the project. Potential Supplemental Services include:

- Programming

- Multiple Preliminary Designs

- Measured Drawings (Existing conditions)

- Existing Facilities Surveys

- Site Evaluation and Planning

- Building Information Model Management

- Development of BIM Model for post-construction use

- Civil Engineering

- Landscape Design

- Architectural Interior Design

- Value Analysis

- Detailed Cost Estimating

- On-Site Project Representation

- Conformed Documents for Construction

- As-Designed Record Drawings

- As-Constructed Record Drawings

- Post-Occupancy Evaluation

- Facility Support Services

- Tenant-related Services

- Architect’s Coordination of Owner’s Consultants

- Telecommunications / Data Design

- Commissioning

- Sustainable Project Services (certifications)

- Fast-track Design Services

- Multiple Bid Packages

- Historic Preservation

- Furniture, Furnishings, and Equipment

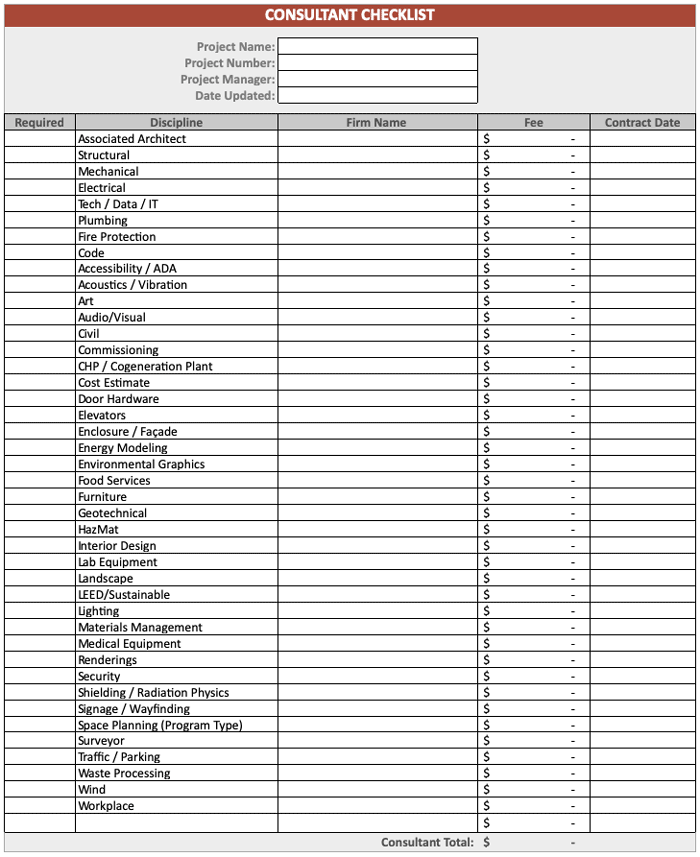

In addition to this list of Supplemental Services as listed in B101-2017, the architect should also be aware of any consultants required beyond structural, mechanical, plumbing, and electrical engineers. Consider the following list when developing a fee, but understand that it is not comprehensive and some of these consultants are part of Basic Services.

- Code

- Accessibility / ADA

- Acoustics / Vibration

- Art

- Audio / Visual

- CHP / Cogeneration Plant

- Door Hardware

- Elevators

- Enclosure / Façade

- Energy Modeling

- Environmental Graphics

- Food Services

- Geotechnical (usually by owner)

- HazMat

- Lab Equipment

- Lighting

- Materials Management

- Medical Equipment

- Renderings

- Security

- Shielding / Radiation / Physics

- Signage / Wayfinding

- Space Planning (Program Type)

- Surveyor

- Theater / Stage / Set

- Traffic / Parking

- Waste Processing

- Wind Engineering

- Workplace

Fees for Supplemental Services can be included in the overall fee or they can be invoiced separately, but it is critical that the owner and architect agree on who is responsible for each service so a proper fee can be developed.

Additional Services

B101-2017 defines the Architect’s Additional Services as required services identified after executing the contract, meaning they weren’t included in the scope of the original contract. Except for issues that are the design team’s fault, the architect is entitled to additional fee and a schedule extension.

The architect is obligated to promptly notify the owner of the need for Additional Services and the owner must approve them before services are started. However, there are some services during the construction phase that the architect must start working on without approval to prevent delays in the field.

Negotiations around Additional Services are often contentious and emotional. Owners don’t like to see their project costs increase, while architects want to be paid for work they don’t believe was included in the initial fee. This is why written documentation of the detailed scope is important. Architects might find it helpful to provide a list of services that are expressly excluded or declined by the owner, especially if those services are commonly included in projects.

In addition, it is important for project managers to be in constant communication with the owner and the consultant team so issues can be resolved before they turn into Additional Services. Early warnings about slow decisions or other delays can help the owner make adjustments in their process so the fee isn’t compromised. It is much better to say, “we can absorb this change, but we need to adjust the process to avoid Additional Services” than to unexpectedly show up at the owner’s door demanding more time or money.

Principles of Architectural Fee Development

There are a few major principles to keep in mind when you develop a fee for service. These tips can become part of a checklist so that you think through the fee thoroughly.

Know Your Value

Firms that demonstrate their value to clients can demand higher fees than those that design commodity buildings. Value comes in many forms and every client is looking for something different so it is important for a design firm to develop their value proposition and focus on it intently. Your value proposition may include:

- Attention-getting design

- Building type specialization

- Cost effective design

- Project management/leadership

- Documentation quality

- Municipality relationships

- Client service

- Specialty knowledge or experience

The list is endless, but you get the picture: have a value proposition and execute on it to the fullest so you will have no problems attracting clients willing to pay higher fees.

Define Scope of Services

When presenting your fee proposal to the client it is very important that part of the package is a detailed scope document. This is often a simple list that includes information on tasks, deliverables, staff, schedule, and reimbursable expenses.

In addition to what is included in the scope, it is equally important to make specific exclusions for items that would normally be included in the scope.

Presenting these two lists, and including them in the contract, protects you in the event of a dispute over what is included in the fee. More importantly, the lists allow the client to ensure that they are getting everything they want and nothing they don’t want. After your client reviews the lists, you can then discuss eliminating scope (reduces the fee) or adding to the scope (increases the fee).

It should be reinforced that providing a detailed scoping list ensures that both the architect and client are in alignment over what the project entails. Think of these as tools to reach a clear agreement, which helps avoid a dispute (and a significant amount of stress) in the future.

Understand Level of Effort

Developing a workable fee requires the project manager to understand the design process of the firm and consultants, but also the client’s decision-making process.

Project manages must stay up to date with how the latest technologies affect their level of effort. For instance, BIM has changed our design process in major ways, one of which front loads hours so that more documentation work is done in during Design Development with fewer hours during the Construction Document phase. An office’s design process (or even a specific design principal’s process) can affect the fee if not managed properly. Consultants can also affect the level of effort so it is helpful to understand their workflow. These are only a few examples of things to watch out for.

The owner’s process directly affects the design team. Certain clients want lots of design studies, while others have a fast-track project with tight deadlines. Many large institutional projects require a full-time construction administration team, some of whom will be stationed in a field office, but smaller residential projects only require regular site observations. Be sure to understand your client’s needs and help them understand how those needs affect the total fee.

Factor in Risk

Risk is one of the key elements that must be understood so it is worth the team spending a fair bit of time evaluating it during fee development and then managing it throughout the project, starting with the project kickoff meeting.

The best way to manage risk is to maintain open and candid lines of communication with all parties (client, architect, consultants, contractor, etc.) from the early fee development phase through project closeout. You can often see problems arising and make adjustments before anyone is adversely affected.

Clients put your fee at risk in many ways. Are they a savvy institution that has the experience to know the architect’s responsibilities or is this a small company who has never hired an architect? Are they litigious? Does their vision exceed their budget? Do they understand the Level of Care and that documents aren’t expected to be error-free? There are many more questions to ask, but the key, as mentioned above, is to manage client risk through communication and education.

Consultants also bring risk. Do they complete their work on time so that the rest of the design team can avoid re-work? Are their fees in line with their competitors? Do they properly manage risk from their side and communicate to you as they see things becoming a problem?

The project delivery method and contractor should also be evaluated for inherent risks that can affect your fee. Fee allocation might need to be shifted within the phases depending on whether the project is design-bid-build, design-build, or if there are fast tracked components.

Also consider the jurisdiction and any permitting risk that must be accounted for. Entitlements in large cities or for major projects might take longer than expected, which leads some firms to do this work on an hourly basis. Complicated soil conditions or zoning requirements might also create more work for the design team.

Finally, two big risks: construction cost and schedule. We touched on these briefly in the client section above, but this is something to keep in mind. If the contract requires the architect to design to a budget, then it is advisable to develop multiple project estimates throughout the design process, but this requires additional documentation and can lead to rework. In addition, schedule can impact fee whether it is too long (more time to explore) or too short (more potential for errors) — both situations can lead to spending fee in the wrong places.

We can’t cover every risk in this article, which is why it is important for an experienced project manager to develop the fee and to get a second opinion from others in the office who can help spot the risks in your plan.

Carry a Contingency

The contingency is your protection against mistakes in your estimating or mistakes on the part of the team, either of which will require additional labor hours on the project. You should always protect yourself with a healthy contingency. If you don’t end up using the contingency then you experience a higher project profit, but if disaster hits the contingency helps the project remaining profitable.

There are a number of ways that a project manager can build contingency into a project – it doesn’t necessarily require a contingency line item. Any time a project manager sets aside money that isn’t assigned to a specific task or expense, this is contingency. Here are a few examples:

- Contingency Line Item, which is clearly identified in the project budget as a dollar value or a percentage of labor.

- An additional “Unassigned Resource” that has hours assigned in the workplan, but no tasks assigned. For instance, you may include hours in the project plan at a specific hourly rate, but not have a specific person assigned or tasks that need to be completed.

- Rounding-up, where the fee is rounded up to the next reasonable whole dollar amount. This will provide extra fee, but usually doesn’t help much so it is often used in conjunction with other methods.

Some project managers may include a 5% or 10% labor contingency in their project plan, but then also include some unassigned hours in addition as another way of keeping a strong contingency. Just be careful that your fee doesn’t become uncompetitive.

As the project progresses, the firm’s accountant may want to release some contingency to profit – this is especially true on multi-year projects. This allows the firm to capture some profit each year and is a reasonable thing to do as the project progresses without any problems. However, keep in mind that many issues may surface during construction so you want to maintain a solid contingency until you are well into construction.

Bottom line: it is important for the Project Manager to set money aside for problems that arise in a project and to continuously monitor that pot of money.

Adjust for Your Tendencies

Even with a lot of planning and experience, an architectural fee is still a bit of a guess. There is no right answer and whether you over- or under-estimate the fee can come down to your own personal tendencies with planning.

One of the most important traits you can have as a Project Manager is self-awareness. This applies to dealing with staffing or client issues, but it is also important when developing fees. You need to understand if your fees tend to be aggressive or conservative.

If you tend to be too conservative, your fees will be too high and you may have trouble getting work in a competitive environment. On the flip side, being too aggressive may earn the job, but you will have trouble managing the project to profit.

A second opinion from a colleague and using multiple methods of fee development will help ensure a successful outcome. Likewise, understanding your tendencies allows you to adjust your fee assumptions as you move through the process.

Monitor Metrics and Historical Data

Historical metrics allow you to check your assumptions against completed projects at your firm. The metrics used can vary across firms, geographic locations, and project types.

Some important metrics might include:

- Construction Cost per Gross Square Foot

- Architectural Hours per 100 Gross Square Feet

- Average Hourly Rate on a Project

- Gross Design Fee per Gross Square Foot (includes engineering fees)

- Net Architectural Design Fee per Gross Square Foot (doesn’t include engineering fees)

- Percentage of net fee spent per project phase

Once you have developed a list of similar projects at your firm, you can check your fee assumptions to see if your new proposal is on par with previous projects.

Most firms already have a database of this information, but if they don’t you can easily pull reports from most popular timekeeping or billing software. Simply ask your firm’s accountant or leadership team for help. In addition, you should also keep your own log of projects for future reference.

Build Checklists

This is a simple exercise, but can save lots of money in lost revenue over a career. Keep a checklist so you remember to factor in all of the various components that go into a fee. You may also want multiple checklists to cover things like: supplement services options, specialty consultants required, or to simply QA/QC your fee proposal.

Architecture Fee Calculation Methods

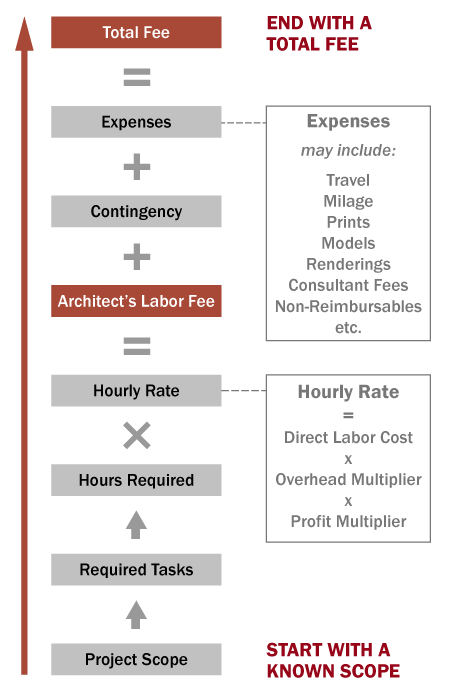

There are four main fee development methods that can be used for project budgeting. There are as many variations on these as there are Project Managers in the world, but just about all of them fall into one of these types.

- Start with a known scope and build up to a fee.

- Start with an acceptable fee and build down to the scope that the client can afford.

- Determine staffing levels and work the allotted hours.

- Use a unit pricing structure like percentage of construction cost or cost per SF.

For the best outcome, it is important to use at least two different methods independently as you develop the fee. Once you arrive at the same scope and cost with two methods, you can feel comfortable that you have estimated a proper fee for the work to be done.

It is also useful to have another person review the fee proposals to make sure that you haven’t missed something, overestimated, or underestimated.

The spreadsheet files you see in this article are available for purchase in the Archtoolbox Store.

Building a Bottom-Up Fee

When you build up from a known scope to a fee, you have generally received a scope from the client. The scope may be conceptual design through construction administration services for a certain size and type of building or it may be a simple feasibility study where the deliverable is a report. The scope may also be as simple as a sketch for a particular detail.

Once you fully understand the client’s scope and expectations, you can determine the tasks required to accomplish the project goals.

Then, based on your experience, you can assign the number of hours required to accomplish each task and multiply the hours by an hourly rate, which provides the total cost of labor.

Once you have the labor cost, you need to add in a labor contingency to account for errors in the work or errors in your estimating process — as we all know, nobody is perfect.

Finally, you need to add money for expenses, which includes consultant fees as well as typical expenses such as travel, prints, models, and renderings. In addition, you should account for non-reimbursable expenses like team lunches, team outings, or other items the client will not pay for directly.

Bottom-up fee development tends to result in a higher fee than the owner is willing to pay for so adjustments should be made as you work through the other methods.

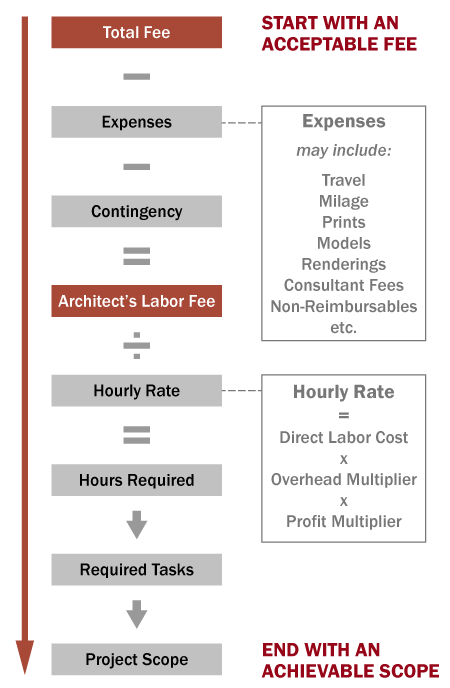

Building a Top-Down Fee

Another way of developing a fee is to start with a dollar amount and work down to the scope. This may be used when a client has a set fee they can spend for a project — for instance, they have $20,000 to spend on a feasibility study.

Start with the acceptable fee and subtract for expenses and contingency. This will leave you with a dollar value available to use on labor.

Divide the money available for labor by the average hourly rate, which will give you the total number of hours available for the project. Those hours then get distributed to the various tasks required to complete the project.

Once the tasks have been developed, it is important for the architect to review them with the client. That way, the client understands what level of deliverable they can afford for the money they are willing to spend. If there is a discrepancy between their expectations and what they can afford, a negotiation takes place, which leads to a final scope and fee agreement.

Be aware that a top down fee development can lead to an overly optimistic fee that is not achievable.

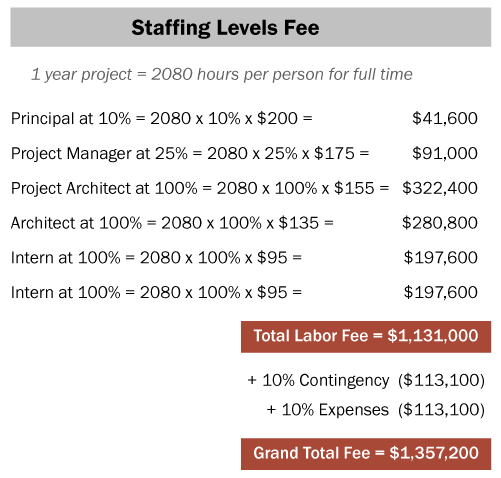

Building a Staffing Level Fee

Another very simple method for developing a fee for service is to simply assign a certain staffing level to be used as needed to accomplish tasks.

This may be applicable for an open-ended consulting assignment where the project team works on whatever is needed during the time they have available on a project. It may also be used on very large projects where you cannot easily develop a list of tasks or the number of hours needed to complete the tasks. For instance, a 1,000,000 SF project cannot be broken down into individual tasks during fee development because the design phases can last for a couple of years or more.

The idea is to develop a team based on your experience on similar projects. Historical data or firm metrics are critical to getting the fee correct. Some firms may have data that indicates the number of hours and average billing rate for each design phase on projects of a similar size.

The project manager identifies the team and the percentage of their time that will be assigned to the project. This leads to a number of hours per week or month, which is multiplied by the hourly rate to get to a fee for labor.

Then a contingency is added and expenses are accounted for, which leads to a total fee.

Building a Unit Cost Fee

Unit pricing is the fourth method for developing an architectural design fee. In this case, you will determine the unit of measure and then apply a specific rate or value to each unit.

The most common form of unit pricing that architects use is the percentage of construction cost, where the gross design fee is anywhere from 3% to 15% (or more) of the total cost of construction. It is important to have historical data to confirm your assumptions on the percentage to use. In addition, the percentage varies based on the size and complexity of the project, and owners often set expectations based on their own metrics.

Another unit pricing method that can be used is hours per 100 square feet of building. The architect can use historical data to determine the number of hours needed to design each 100 SF of building and then apply an average hourly labor rate to determine the design fee.

Other unit pricing methods may include dollars per drawing or rendering, hours per drawing (multiplied by an average labor rate), or labor dollars per square foot. These methods carry the risk of missing scope or underestimated effort.

As with any method, you must add a contingency amount and include consultant fees and any other project expenses.

Always Use Multiple Methods

We have just reviewed four methods of developing a design fee. Each method has a specific use depending on the starting point or information available. However, most projects can benefit from using multiple, or all, of the methods to verify that your fee will be successful.

In order to confirm the assumptions of one method, a second (or third) method should be used to verify that you are in the right fee range. As you work on your fee with another method, you will begin to discover where assumptions are missing or where the data needs to be tweaked. No one method will provide an ideal fee. Rather, the ideal fee will come from using multiple methods and adjusting them until they align.

Never rely on your first iteration of a design fee. You will inevitably under- or over-estimate dollars, hours, expenses, or some other unknown item. Always test your assumptions with other fee development methods.

Get a Second Opinion

It is advisable, if possible, to have at least two different people develop a draft fee and then work together to get alignment. At the very least, another person should check the assumptions (and the math) you have made and confirm that they agree with the final number.

Until you have enough experience developing fees, you will undoubtedly leave holes in the fee or you will add in so many contingencies that the fee will be unreasonable. As you gain more experience, it is easy to become complacent and forget a consultant or a large expense. This is why collaboration is necessary.

It is also a good idea to test your fees with someone who thinks differently or goes about fee development in a different way. This will help validate your assumptions and it is very comforting to know that two people got to the same number in different ways. As a side effect, you will both learn from each other, which will enhance your skills.

Firms should develop a policy that no fee proposal goes to a client without a thorough review by another person. This rule would apply to the most senior partner down to the most junior project manager.

Example Worksheets

Every firm and every project manager have their own preferred worksheets for preparing a fee. These have been developed over years of experience and they understand the nuances of their preferred structure. Here are some examples:

The Role of Negotiations in Fee Development

Do not be disappointed or surprised if your initial fee proposal to a client is rejected. The first fee presentation is only a starting point and serves to align the architect’s and client’s understanding of the project.

Sometimes the client’s expectations are different than what you have used in developing a fee. For instance, perhaps you planned for several design iterations during the feasibility study, but the client only wants to prove that the program elements fit in the available space and doesn’t yet want to move into design.

If there is a misalignment in expectations, you should not start cutting your fee in the hopes of getting the job. Instead, you should have a conversation with the client where you discuss your assumptions and their assumptions so you can come to an agreed scope and fee.

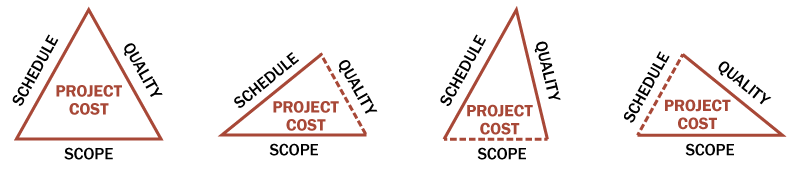

Keep in mind that project cost is a triangle with the scope, schedule, and quality occupying each side. If you adjust one side, another side (or two) need to also adjust. If the scope gets bigger and the schedule stays the same, the quality may suffer. The idea is to achieve balance.

AIA Recommended Fees

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) had long provided schedules of recommended architectural fees based on a percentage of constriction cost, building type, and complexity. The AIA also prohibited its members from competing on price. This led to the U.S. Government filing anti-trust lawsuits against the AIA.

The AIA and U.S. Government agreed to two consent decrees, one in 1972 and one in 1990, that prohibit the AIA from recommending fees and allow architects to compete for work based on fee. The Avery Review has a thorough article about the antitrust allegations made against the AIA.

Typical Architectural Fees

Even though the consent decrees mentioned above don’t allow for the AIA to recommend fees, many people still want an understanding of typical architect fees.

In fact, many organizations use fee tables to help set fees when they hire architects. For instance, Florida has an online fee calculator for Basic Services that factors in project cost and complexity. Many other states, universities, and institutions also have similar charts for Basic Services fees; however, most leave room for the architect to negotiate based on the value provided.

As the cost of the project increases, the fee as a percentage of construction decreases. This makes sense when you factor in economies of scale. Small projects still require all of the same services as a large project, but don’t get the advantage repeatable components.

Likewise, the fee percentage increases as the project complexity increases. This is more obvious since a complex project requires more rigor, additional details, and more on-site visits to ensure proper coordination. In addition, special expertise if often required so the architect may hire additional consultants, even for Basic Services.

Architecture fees for renovations are usually higher due to the additional work required. The design team must verify existing conditions and develop creative solutions that blend the new work into the old work safely and elegantly. Expect renovation fees to be 2% to 4% higher than for new work.

Finally, it is important to understand that buildings have become more complex over time. As recent as thirty years ago, we weren’t as concerned with resiliency, sustainability, and health as we are now. Building systems were much simpler to specify and design. Even waterproofing technologies have advanced and require a deeper level of care than in the past. Our tools have gotten better, but the work required to design a building continues to increase.

Commercial

Commercial projects usually have lower fees on a percentage basis than residential because they benefit from economies of scale at both the design and construction level.

Design fees for warehouses, parking garages, core and shell developer buildings, and other simple buildings can range from 3% to 9% of construction cost. Fully fit out office buildings, schools, and hotels may be in the range of 4% to 10%. Complex buildings like hospitals, laboratories, and other specialized facilities can range from 5% to 12%.

Keep in mind that these are estimated ranges for Basic Services. Project conditions, location, market, and the design aspirations of the owner will impact the design fees.

Residential

Residential projects tend to have higher architectural fees as a percentage of construction cost, especially when you look at custom homes with exacting standards. Many projects have custom details specific to only that project and owners tend to be more particular about the design. In addition, residential projects don’t benefit from the economies of scale you see in large office buildings with repeatable details.

Architectural Basic Services fees for single-family residential projects can range from 8% for large and expensive homes up to 12%+ for small intricate projects. Like commercial projects, these percentages fluctuate based on market factors as well as owner requirements.

Purchase Guide and Spreadsheet Templates

The guide above is available as a PDF download along with the four spreadsheets displayed in the article. You can purchase it in the Archtoolbox Store.

Sources

PSMJ Project Management Training Course

Article Updated: August 22, 2021Help make Archtoolbox better for everyone. If you found an error or out of date information in this article (even if it is just a minor typo), please let us know.

Subscribe to the Archtoolbox Newsletter

Receive a curated email with industry news focusing on practice, leadership, technology, and career growth.

Helpful Tools for Architects and Building Designers

BBToolsets

Bluebeam Tools and Templates for Architects - Customized by Architects for Architects.

Fee Development Tools

The Archtoolbox Guide and Templates for Developing a Fee for Architectural Services.

Negotiate a Raise

The Archtoolbox Guide to Negotiating a Salary Increase

Related Articles

- Construction Schedule Methods

- Architecture Project Planning: Kick Off Meeting

- Construction Project Delivery Methods

- Best Architecture Reference Books

- Best LEED AP Exam Prep Materials

- Free Online Building Codes

- Best LEED Green Associate Exam Prep Materials

- Architect Registration Exam (ARE 5.0) Study Guide Reviews

Newest Articles

- Becoming a Licensed Architect in the United States

- Civil Engineering Plan Symbols

- Ethics in Architectural Practice

- Civil Engineering Abbreviations

- Steep Sloped Roofing Systems